My work was an elaboration of a Tagorean sentiment

Por: Devapriya Roy

Toook from scroll.in

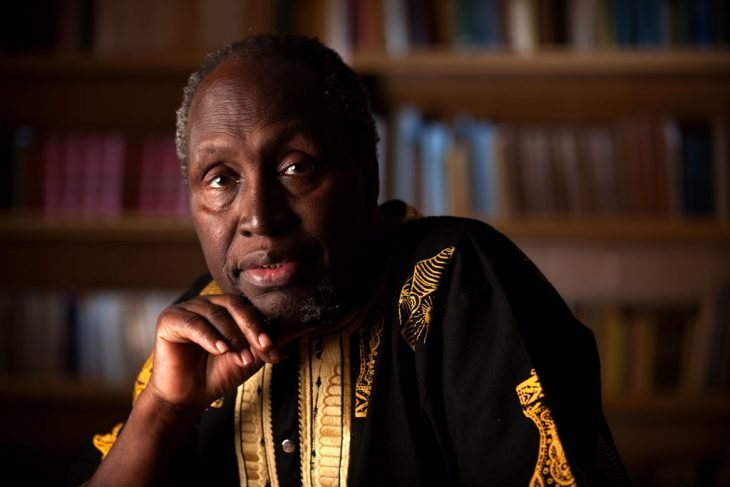

One of Africa’s greatest writers, the Kenyan Ngugi wa Thiong’o, was recently in Delhi for the ILF-Samanvay Translations Series of talks organised by the India Habitat Centre and Seagull Books. When he agreed to speak to Scroll.in, the besotted fan girl that I am, I went to meet him for our chat clutching my battered college copy of Decolonizing the Mind. Excerpts from the conversation:

Professor Ngugi, I must begin by telling you about my encounter with your cult classic, Decolonising the Mind. We read it in class in our MA days, and I must tell you we were all shaken by it because we were studying English literature, and some of us, at least, would go on to write in English too. We all had very rich literatures in our mother tongues; and yet, some of us knew as early as the time that we’d choose English as the language of creative expression. In my mind, I justify it in many ways. I am speaking to other Indians whose mother tongues are very different from mine. Etc. But you had made us all – cocky young things with notions – very uneasy.

I must clarify, I have no problem with an individual person writing creatively in a language of their choice at a certain time. But the reality is that we don’t do that simply as a matter of choice. In some ways, it is a choice already made for us. It was made for us a long time ago by the colonial situation. And it was not for any altruistic reasons...

Right. And not to talk back to the empire either – rather, it might well be to be published abroad.

The reality, of course, is that speaking across communities can happen through translation. Just today, I received a copy of my novel Petals of Blood translated into Hindi, and, last week I was in Hyderabad and attended the release function of another translation of Petals of Blood – into Telugu. I wrote Wizard of the Crow in Gikuyu...

And you translated it yourself?

I did, later. Although it could have been done by anybody. And potentially it can be available in any other language in the world – in fact, it already has been translated into many. Though it’s through what they call “relay translation” because they often take from the English text. You see, in usual circumstances it would be normal for us to be able to write in our own languages, communicate with others speaking other languages, and, under normal circumstances, it would all be fine. But we are talking about the consequences of our colonial past...

The burdens of our histories...

And those histories include the fact that there are very few resources, particularly in Africa, put into the development of African languages, and fact is, whether you like it or not, English is still very much the language of power in Africa. Whether you want a job in the administration, the marketplace or the university, whatever, it is believed English, will give you an edge. In such a situation, automatically our policies change, and more resources are put into teaching and learning English. If our languages were made to matter, if knowing another language is rewarded in real life – in somebody’s promotion, for instance – things might change. People are psychologically tuned to give resources to English (or French or Portuguese depending on history) because these are seen as languages of power.

And I think the rise of America post World War II solidified the role of English (though in America, English had nearly lost out to German!).

Exactly, English was the language of power in the days of the British Empire and now in the times of the American Empire!

Published at March 27th, 2018