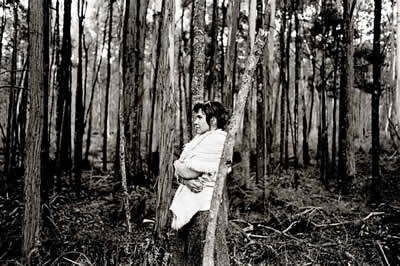

26° Medellin International Poetry Festival. Judith Crispin (Austalia 1970)

Photo by Jason Blake

Judith Crispin was born in Sydney, Australia in 1970. She is a poet, photographer and composer. She studied Music at the Conservatory of Music in Melbourne and at the School of Music in Canberra before earning a doctorate in Composition and Musicology at the National University of Australia in 2004. Following her doctoral studies with Larry Sitsky, Judith continued to study composition with Emmanuel Nunes in Paris in 2005.

She has received a number of awards and prizes including the International Composition Prize Opera Nancy Van de Vate 2004 and the Composition Prize in tribute to Harold Allen 1996 and 1997. From 2002 to 2007 she worked on a project with Larry Sitsky to preserve the Australian compositions. This project has produced a series of scores published by The Australian Keys Press, Perth, Australia. From 2000 to 2004 she worked as a teacher in musicology and composition at the Music School of Canberra, ANU. Judith has worked as a guest professor at the American University in Cairo and as an occasional interviewer for the Department of Oral History of the National Library of Australia. She currently teaches composition and musicology at the University of Southern Queensland.

Light Trails of Henry Jackamarra Cook

Law is a grey kangaroo dancing

the thin landscape of Henry Cook into being,

somewhere in the Tanami,

where knucklebone winds scrape bare rock

and Henry stands marsupial

in the firelight's weird.

In Lajamanu, tin houses edge the street.

No one is outside,

no one.

In the arts centre, old ladies paint seed-dreaming.

Breeze lifts the hem of a curtain,

then stillness.

It is still.

Henry doesn’t paint anymore. He sits alone,

watching ceremony from the 1970s.

Everyone in the videos is dead now, except him.

And the dead are in the desert,

faceless as the desert is,

and as remote.

Ten years ago it seemed nothing to walk

three days to his sacred country,

granite country,

where great salt lakes exhale their thirst

over spinifex and sand,

the rattling sun.

But arthritis and cataracts have caged him.

Inside the arts centre,

the lights are switched off.

We drag chairs across a concrete porch

to watch the Tanami darken, shelf clouds

seal the crater at Wolfe’s Creek.

Rain wakens on his tongue

the angular syllables of displacement.

And home is the desert breathing over itself by night,

erasing tracks of all who walk there—

night’s emu rising savage in the milky way,

and eyes, eyes in the granite mines.

One day, he tells me, I'll walk out

to my country and never come back.

At town’s edge, a kangaroo left by poachers.

Red dust thickens its pelt, as the red dust lies thick

on Henry's raybans,

stiffening his white hair to wires.

I photograph him disemboweling the buck,

its intestines knotted to ritual marks—

Henry and his flayed brother, backlit

against chained ridges,

and the last sun rearing.

Law is an old man dancing

the grey kangaroo into being,

sewing him back into the desert’s body,

into his own body, ochre and growl,

a hunting boomerang beaten on the ground.

Night erases this landscape–

slow trees, sand,

the saltbush has gone.

Just Henry’s heels rising and falling

along a windscored track,

utterances of a language which belongs to him

and to which he belongs.

Tomorrow, the catfish waterhole

will stretch his white hair out elastic,

as telephone wires vanishing into the Tanami.

Mud returns to him

the cool slow memories of country

before the missions, before diabetes and grog

shrank his ancestors down so small,

he holds them in a single cupped hand

like fireflies, tiny comets

crossing in the black.

Tomorrow he'll thread gumleaves

through the hole in his nose,

and say, photo me like this Nangala

I am a beautiful man.

Sommernachtstraum

—for Irene Lamprecht

I love you

from a fear of loneliness,

said the Minotaur.

Perhaps he’d not spoken,

but she’d known it

from the restless sound of his bellowing

deep in the ornamental garden.

She sees him grown tiny with distance;

a figure with weighted head,

disappearing into an erotica of trees.

And for the longest time

they circled near to one another.

She, in the avenues of burned Lindens,

the shadows cast by cold war television antennas;

and he, in the Dämmerung,

the mythical spaces of Goethe and Heine,

touching reality only as something profane:

the imp perched on a sleeper’s chest

or a half-transparent figure seen in fog

by early morning cyclists.

She keeps a photograph of him

taken in his studio

he is painting nature morte,

halved fruit in an antiquated style,

but she liked how light fell across his hand

and how his body and hers were separated only

by paintbrushes in a jar

and cigarette smoke.

The picture frame breaks and is never mended.

She fills her apartment with orchids

and recordings of Peking opera;

but in the nights,

near Teufelsberg, where there are no Minotaurs

and lichen falls like old woman’s hair,

she lies between hulls of abandoned cars

searching for satellites.

In Krakow

Before the thousand-eyed cathedral,

a homeless man sinks to his knees

wreathed by gliding breasts of pigeons.

He is singing almost without sound

Panis Angelicus.

Light fails and the birds,

air lifting through their feathers like breath,

in vain use their silence to reach him.

The Wedgetails

“The sea is not less beautiful in our eyes because we know

that sometimes ships are wrecked by it.”

(Simone Weil)

King tide, January 1976.

The beach is an ivory line between spruce.

Aeroplane-armed, my brother runs

through waist-high grass,

sunlight skittering around him,

lifts static in his thin hair.

From open sea, a kurruwarri wind,

lungs of the breath that formed us,

that wove us together in secret;

when we were magicians

and read auguries in tongues of sand.

Mud creepers and whelks—

the sea returns its dead into our keeping.

Mum’s paisley sleeves billow

as she waves us in,

the sky flexing, clouds dilate

to anvils above our tent,

and I remember how the sea withdrew.

Through our Valiant’s rear window

treelines thin to spinifex,

the ochre bulls of dust rise,

shoulder to shoulder, where we pass.

In the microsecond before dark

a wedgetail spirals to light

between gigantic clouds.

It is night. The radio emergency channel

mutters under ululating gales.

My brother sits between front seats

his face tinted green by the dash

is crossed by fishtailing windscreen wipers.

And in the south-west, long ant-trails of semi-trailers

wind away and vanish.

Our breath pools opal on the windows.

We watch for shapeshifters:

ochre-striped and dark at the breast—

holes where the rain does not fall,

(mirlalypa) we watch for holes in the rain.

To this sanctum of wind and silence and wind

we arrive endlessly,

always following road trains,

snaking endlessly into cyclone—

omen-clouds advance like icebreakers,

and into the last slivers of light

the wedgetails come folding in.

I am Freyja

I am Freyja of the ice fields,

following a narwhal’s tusk

through diamond-threaded air—

for he has retracted speech into his jawbone.

And if in sleep, he grazes my naked hip

he will not wake me.

In all the rooms of our house,

snow is falling.

I am Freyja of suburbia,

watching a hills-hoist rotate its shadow

into a caribou’s shape,

its velvet nostrils lifting in wind.

And dusk is a cinder path between rooves,

the min-min of headlights on the Parkway,

where a hooded woman walks her dog

in the last light leaving.

I am Freyja, with the driver’s door left open,

running back to a rabbit on the road.

Its body unmarked,

one eye turned upward to the moon,

Vega, Europa,

the immense indifference of space.

And he is waiting in the car like a stranger,

streetlights flooding the windscreen,

and we have already begun

not to belong to each other.

I am Frejya

whatever happens now won’t matter.

in the cafe of our Fimbulvetr

he will buy me an espresso

and tell me it’s over.

Gamma

Nights of winter,

of cloud,

mauve-grey and thin.

Mangroves drop

in the frost-formed creek,

water climbing in darkness.

A white dog

crosses the clearing—

stops, startled by apparitions.

He rotates an ear

in that enormous stellar bowl—

and I know this place,

this stone-lit track

and snarl of sloping trees.

My brother,

sleep has stolen from us this landscape

this sky wandered by satellites

and moist, heavy winds.

A raven spits on a hip of road,

its disembowelled fox thrown from reach

by passing lorries.

And I knew you then, my brother.

I knew your stillness

and did not flinch

at the crash of midnight birds.

In fog, in scarce Pleiades light,

I tasted salt on your mouth

and in your beard,

the dawn.

Published on April 7th, 2016