Me, Wars, Exiles and My Long Poem

Por: Adnan al-Sayegh

Edited by Dr. Jenny Lewis - poet, teaches poetry at Oxford University

In my early poetic beginnings and later, I was known for writing short and very short poems. I was fascinated by epigrams, or ‘quick as a flash’ poems that capture an idea or a form - in a world where everything happens fast. I never imagined that I would one day become the author of the longest poem in Arabic history, and perhaps in the world - I mean my two poems: Uruk's Anthem, 1996 and its sequel, The Dice Of The Text, 2022. I don’t know how or why I fell in love with poetry. It is a beautiful, tiring and astonishing dilemma that has opened many worlds, fantasies and journeys at life’s margins for me. The beginning of my extended poem Uruk’s Anthem and its ending in The Dice of the Text are very different in time, place, mood and vision. I started writing Uruk's Anthem, or it started writing me, in 1984, in an abandoned stable on a dangerous border in the years of the grinding Iran-Iraq war. At the time, I was in my late twenties. I finished it, or it finished with me, in 1996 in Beirut after escaping from my homeland. In the same year, 1996, I began composing The Dice of the Text which I finished, or it finished with me, in 2022, when I was in my late sixties. Thus the lure of the long poem has captivated me for nearly 40 years. Faced with the constant threat of death, continuous wars and the absurdity of life as well as the tyranny of power, oppression and strict control, and in the face of the silence of the world and the silence of the Lord, I had to record all that screaming and wailing in me secretly in the form of a long and bitter delirium. I found that writing in this open form was a creative outlet for me. I also found in poetry the strength to confront war, and stand against the wars and oppression of my own country until today, the Russian-Ukrainian war, and the genocide that we are witnessing on TV screens. It is disastrous in every sense of the word! The scenes of death have brought me back again to the question of poetry and existence: how does one human being have the right to confiscate or kill another human being, and how does a state have the right to confiscate, kill or rob a state. Are we in the law of the jungle? The world today, in 2022, is at the height of its development and its aspiration for freedom and progress, and also at the height of great cosmic challenges: the environment, diseases, pollution, terrorism and famine among them.

I had previously written: 'Creative writing, in a time of tyranny, is like walking through minefields.’ Today, as I come out of the minefields ‘unawares’, I find that creative writing is an act of creative resistance. Every act of love, hope, or creativity in times of war carries within it the power of creative resistance. I felt compelled to write and write and write. The more they tried to suppress me, the more I wrote. I was writing in secret, and because it was not for publication, it was completely free and bold. I really didn't know at what moment a shell or bullet could fly through my head. I just grabbed my pen and paper, so that pictures, shapes and words rained down on me in a fast flow. Was it inspiration, or pressure? Pain or oppression? Or something I didn’t know yet. And always, day or night, I kept slips of paper or a small notebook and pen to write down the sentences or thoughts that came to me in a hurry before they disappeared. When I re-read them, I found some of them very strange and amazing, and some of them like a dream that I cannot explain (my friend Jenny and some of my other translator friends asked me a lot about this, but I was confused and did not have an answer or an explanation for the picture or the phrase). It was as if a mysterious force wanted me to write the secret history of war – writing down the shades of ideas and forms and the things that will be neglected by historians and generals when the war ends and they share out the medals, victories and defeats. Iraqi literature is filled with narratives. But Uruk's Anthem was like a new attempt to recount war in poetry. Perhaps it followed in the footsteps of Scheherazade in the 10001 Arabian Nights as she lengthened the stories and wove them with poems and magic in order to avoid the sword of King Shahryar that hung over her tender neck; or as if I was Sinbad the Sailor, passing through dangerous seas, not knowing where I’m going, armed with the power of adventure and discovery that is poetry.

I found myself immersed in tradition to a great extent, devouring the contents of old bookshelves from eastern and western cultures. Then I faced this heritage – history, religion and political, social and cultural systems – that brought us to where we are. I faced this heritage, with questions, arguments, and protest before embarking on my new poetic enterprise called Uruk’s Anthem (1984-1996 Baghdad / Beirut / 550 pages). It deals with war, biography, history, myth, etc. I took inspiration from the Epic of Gilgamesh in the first place and the Sumerian, Akkadian, Babylonian and Assyrian heritage. In addition, I looked to other epics such as the Mahabharata, the Ramayana; the Odyssey and the Iliad by Homer, The Art of Love and Metamorphosis by Ovid; the Persian Shahnameh by Ferdowsi; the Divine Comedy by Dante and Don Quixote by Cervantes, Paradise Lost by Milton, The Waste Land by T.S. Eliot, among others in addition to contemporary poetry in the Arab world and internationally including Cafavy, Mahmoud Darwish and Yannis Ritzos.

Then followed my new book The Dice of the Text (1996-2022 Beirut/London) which delves deeper into the heritage of the past on one hand, while on the other hand exploring the latest contemporary Arab and European poetic and visual forms, leaving the dice to make its own path, using different forms and inventing a new text that summarizes the history of human pain. It is a long text in a single volume of 1,380 pages, that took more than a quarter of a century to work on. The Dice of the Text ploughs the unspoken in the margins of Arab-Islamic and world history. It is a provoking and dangerous reflection on our contemporary reality, excavating, inquiring and investigating many concepts in politics, religion, gender, mythology, sociology, heritage and literature. I cherish these two works because they shared with me the paths of my life and my poetry, lived through in all the details, and narrated and recorded with honesty, freedom and boldness everything that went through me, my country and the world. As rhythm (and sometimes rhyme) dominate my first work, the flow of words and ideas in the form of a prose poem and an open text (sometimes with less rhythm and rhyme) is more apparent in my second work. And here I am, after about two thousand pages, I do not know where the words come from with their ideas and forms and how they are confused and overlap. My experience in these two works has taught me to write – freely and honestly – your first word and your first sentence, then leave the rest to the wind or to the music and the days.

Years later, and during my many travels in Arab and European exile, I landed in London. By extraordinary chance, I met a British poet at a poetry evening who was talking about Enheduanna, Gilgamesh, Inanna and Uruk. These living mythical symbols brought Jenny Lewis and me together on a long journey of shared poetry and to many events and readings in the UK and abroad. Our shared love of the ancient Near-Eastern world and culture developed into a major project to translate extracts from Uruk’s Anthem in co-operation with family and friends, including the Palestinian-Lebanese writer, Ruba Abughaida. After eight years of diligent work and continuous discussions, our work was published in a wonderful edition by the Welsh publisher Seren in 2020 as Let Me Tell You What I Saw. Despite the Corona pandemic our online book launch reached several hundred people globally and was followed by many further readings and events, assuring us once again of the strength of poetry to reach and challenge.

With Ruba, and these same family and friends, I have also translated many of Jenny’s poems. Between us we have built beautiful and brilliant bridges of light between two languages, two cultures, and two worlds. Without translation the other cannot be understood and communicated with. Together, we have witnessed a huge number of beautiful responses from a diverse range of readers and listeners from all over the world – most recently at the marvellous StAnza Poetry Festival 2022 in Scotland. Literal translation of poetry kills its soul and dampens its glow (which some purists do not understand). But the poet – the true artist – when they transfer a text by artistically understanding and digesting it into another language (which is what the act of translation is) they create it anew, giving it another form and another creative life, so that it is on a level with original music, paintings or theatre performances, and this is what I recognised in our translation of extracts from Uruk’s Anthem as Let Me Tell You What I Saw.

From Long Poem Magazine, UK. ISSUE 28 | Autumn 2022

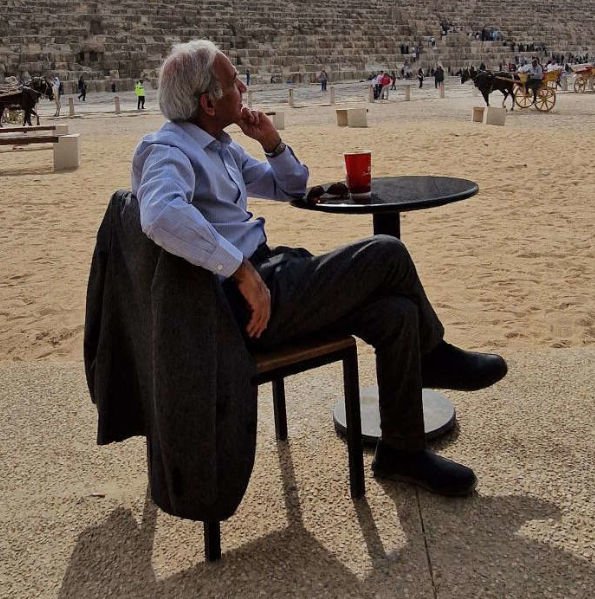

Adnan al-Sayegh was born in al-Kufa, a city on the banks of the Euphrates in Iraq in 1955 and is one of the most original voices of his generation of poets. His poetry denounces the devastation of wars and the horrors of dictatorship. Adnan has published thirteen collections of poetry, including the 550-page Uruk's Anthem (Beirut 1996), the 1380-page The Dice Of The Text (Beirut, Baghdad 2022) and very short poems Glimmerings… Of You (London, Baghdad 2024)

He left his homeland in 1993, lived in Amman, and Beirut then took refuge in Sweden in 1996. Since 2004 he has been living in exile in London. He has received several international awards; among them, the Hellman-Hammet International Poetry Award (New York 1996), the Rotterdam International Poetry Award (1997) and the Swedish Writers Association Award (2005), and has been invited to read his poems in many festivals across the world. His poetry had been translated into into many languages.