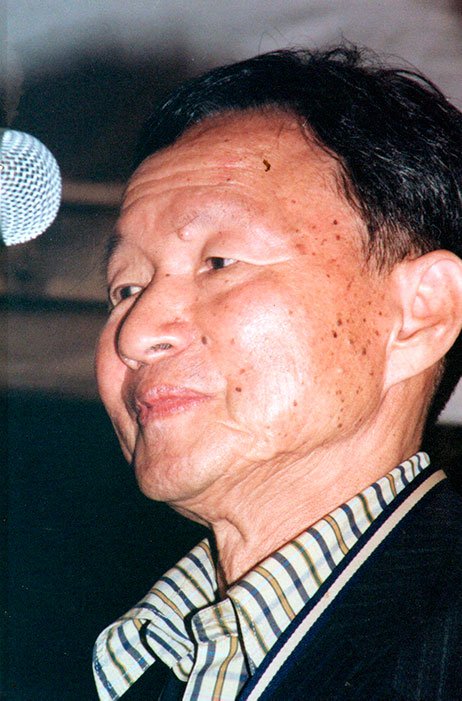

Shin Kyong-Rim, South Korea

Por: Shin Kyong-Rim

On a Winter´s Night

We´re met in the back back room of the co-op mill

playing cards for a dish of muk;

tomorrow´s market-day. Boisterous merchants

shake off the snow in the inn´s front yard.

Fields and hills shine newly white, the falling snow

comes swirling thickly down.

People are talking about the price of rice and fertilizers,

and about the local magistrate´s daughter, a teacher.

Hey, it seems Puni, up in Seoul working as a maid,

is going to have a baby. Well, what we have a sniff?

Shall we get grunk? The bar-girl smells

of cheap powder, but still, shall we have a sniff?

We´re the only ones who know our sorrows.

Shall we try raising fowls this year?

Winter nights are long, we eat muk,

down drinks, argue over the water rates,

sing to the bar-girl´s chop-stick beat,

and as we cross the barley-field to give a hard time

to the newly-wed man at the barber´s shop,

look at that: the world´s all white. Come on snow, drift high,

high as the roof, bury us deep.

Shall we send a love-letter

to those girls behind the siren tower hiding

wrapped in their skirts? We´re

the only ones sho know our troubles.

Shall we try fattening pigs this year?

After market’s done

We plane folk are happy just to see each other.

Peeling ch’amoi melons in front of the barber’s,

gulping makkolli at the bar,

all our faces invariably like those of friends,

talking of drought down south, or of co-op debts,

keeping time with our feet to the herb peddler’s guitar.

Why are we all the time longing for Seoul?

Shall we go somewhere and gamble at cards?

Shall we empty our purses and go to the whore-house?

We gather in the school-yard, munch strips of squid with soju.

In no time at all the long summer day’s done

and off we go down the bright moonlit cart-track

carrying a pair of rubber shoes or a single croaker,

staggering home after market’s done.

Farmers’ dance

The ching rings out, the curtain falls.

Above the rough stage, lights dangle from a paulownia tree,

the playgroung’s empty, everyone’s gone home.

We rush to the soju bar in front of the school

and drink, our faces still daubed with powder.

Life’s mortifying when you’re oppressed and wretched.

Then off down the market alleys behind the kkwenggwari

with only some kids running bellowing behind us

while girls lean pressed against the oil shop wall

giggling childish giggles.

The full moon rises and one of us

begins to wail like the bandit king Kkokchong; another

laughs himself sly like Sorim the schemer; after all

what’s the use of fretting and struggling, shut up in these hills

with farming not paying the fertilizer bills?

Leaving it all in the hands of the women,

we pass by the cattle-fair,

then dancing in front of the slaughterhouse

we start to get into the swing of things.

Shall we dance on one leg, blow the nallari hard?

Shall we shake our heads, make our shoulders rock?

Shin Kyong-Rim was born in 1935. His literary career dates from the publication of three poems, including The Reed in 1956 but after that he published nothing for a number of years, immersing himself instead in the world of the working classes, the "Minjung", and working as a farmer, a miner, and a merchant. His fame dates mainly from the publication of his first collection Nong-Mu (Farmers' Dance), in 1973. Shin Kyong-Nim has continued to play a leading role in the world of socially involved poetry. He has served as president of the Association of Writers for National Literature, and of the Federated Union of Korean Nationalist Artists. Other volumes of his poetry include Saejae, 1979; Talnomse, 1985, Namhankang (South Han River, 1987), Kana nhan sarangnorae (Song of poor love, 1988), Kil (Road, 1990), Ssurojin cha ui Kkum (Dreams of the fallen, 1993), Halmon i wa omoni ui silhouette (Silhouettes of grandmother and mother, 1998). This last volume received the 1998 Daesan Literary Award for Poetry. He was published too recently to be included here. He has also published several collections of literary and personal essays. He has traveled widely collecting the popular songs that have survived in Korea's rural areas and his poetry is deeply marked by the rhythms of traditional Korean music as a result. An English translation of Farmers' Dance was published in this same series in 1999.